While writing this book review on what makes the Dutch the “The Happiest Kids in the World”, I was curious: What do you think makes for happy kids? What do you value and try to build into your children’s lives to help them feel happy? Do you think happiness is important, or are other factors more important in children’s lives? Please share your comments below.

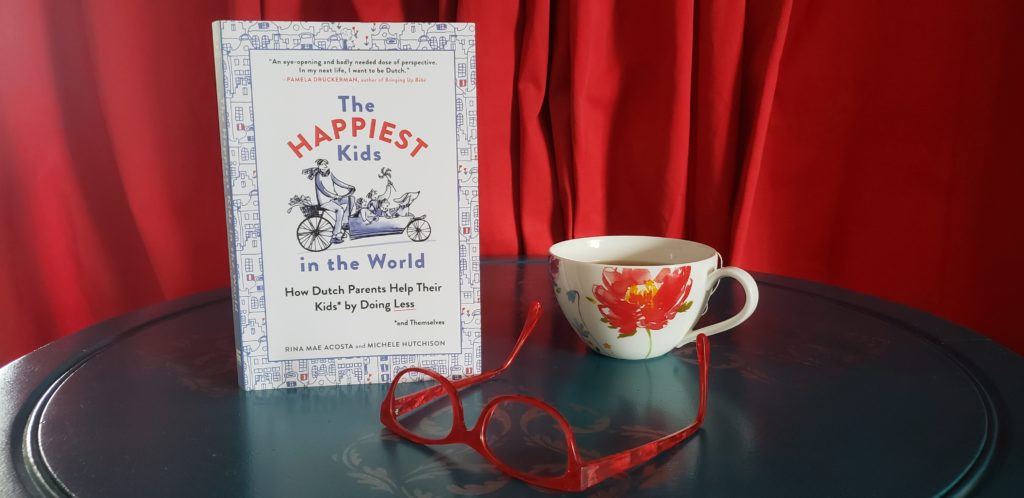

The authors, Rina Mae Acost and Michele Hutchison, are both expat mothers from the US and UK enjoying the perks, and adjusting to the differences of, raising their children in a country with a culture and language different from their own. They have together highlighted the key parenting approaches, practices and theories prevalent in the Netherlands to help us gain insight into how Dutch parents raise the “happiest kids in the world”.

Rina and Michele set the stage for the book in opening with their founding premise by citing a fabulous quote from Oscar Wilde: “the best way to make children good is to make them happy“. They aim to make the case that through a more relaxed parenting style that involves a lot of play and freedom for their kids, that their kids will be happy, healthy and confident.

A fun yet powerful read

I very much enjoyed this fun, light read that packed a punch in the strength of the messages that the authors convey on the Dutch parenting style that brings their kids, as well as the parents themselves, so much joy. For the most part, these are the simple pleasures in life, like outdoor play, camping, visiting friends. Many readers may recognize many of these highlights in their own childhood thirty or more years ago. I appreciate the authors time and energy in writing this book to shine a spotlight on encouraging parents around the world to bring more of the simple pleasures into our kids lives, and to get parents and those involved in kids lives talking about them again.

To back their claim with data that Dutch kids are the happiest in the world, the authors rely on a UNICEF report in 2013 that shows child well-being in the Netherlands is ranked number one among rich countries. This is calculated on five indicators including: material well-being; health and safety; education; behaviours and risks; and housing and environment. The Netherlands scores very highly in all these areas. In contrast to the Netherlands ranking first, the UK ranks 16th of 29 countries ranked, which also bolsters their belief that life as a parent and kid in the Netherlands is much better than in the UK. Of interest, I also had a look into a similar 2007 report by UNICEF and the Netherlands was again ranked number one of the rich countries according to their six indicators – so there is a pattern emerging over time.

How this review is organized

To give you a few signposts to help navigate through this review, I’ve started with an overview of the key highlights of the book, then I have provided more details on the 9 main messages I picked up through the book. I then go on to share my thoughts on the comparison with parenting in the UK, and some ideas on how non-Dutch parents could try to incorporate some approaches in the book into their own lives. And, finally, I discuss the question of whether we should also be discussing well-being instead of, or as well as, happiness as an indicator for raising

Highlights of “The Happiest Kids”

Reading through this book I, for the vast part, very much agree with and enjoyed reading of the parenting approach and tools that Dutch parents utilize. The lifestyle choices that they make as parents – and as people are also important, because let us not forget that once you become a parent, you are still an individual adult person! (There is a whole chapter on this). I particularly valued the chapter ‘happy parents have happy kids’ where the authors share the personal freedoms that Dutch mothers retain for themselves, their part-time work that doesn’t attract any stigma and allows them more time for family, themselves and their other interests, friendships and relationships outside of child-rearing.

Since sometimes it’s helpful to read a summary of the book before committing to the real thing, and because sometimes we don’t all have enough time to read the whole book, I’m highlighting some of key quotes below that convey the main messages of the book:

- “They understand that achievement doesn’t necessarily lead to happiness, but that happiness can cultivate achievement”

- “Simplicity: Families tend to choose simple, low-cost activities and take a down-to-earth approach”

- “As the part-time work champions of Europe, the Dutch work on average 29 hours a week, dedicate at least one day a week to spending time with their children, and pencil in time for themselves, too”

- Parents “don’t do for their children things they are capable of doing themselves – they believe in encouraging independence at the appropriate age”

- Kids “enjoy a huge degree of freedom: they ride their bikes to school, play on the streets and visit friends after school, all unaccompanied”

- “there is no tabloid press whipping up parental anxiety, and Dutch parents are extremely good at putting things into perspective”

- “there is less social and financial inequality in the Netherlands than in the US and the UK” and “there was a unified state – school system , so no terrifying gulf between public and private, between the haves and the have-nots”

- “doe maar gewoon is all about doing the best you can. Keep it real!”

- “Trusting the child to make their own choice is a lot less stressful for the parent”

- “you only have one childhood and it lays the foundation for the rest of your life”.

Dutch parents approach parenting “with the aim of simply being a ‘good-enough’ parent. The underlying premise is straightforward: keep calm. Doing your best is good enough.” Accepting imperfections and faults, rather than stressing over them, makes it easier to enjoy parenthood.

1. Taking care of the parents

“The Dutch tradition is to give birth at home, assisted by a midwife and without any pain relief”, in a loving, supportive environment with “no strangers, no bright lights, no clanging hospital equipment” since they believe that “pregnancy and labor are normal events rather than a medical condition”. About 25% of births occur at home and yet the Netherlands ranks sixth safest in the world to give birth or be born. A maternity nurse (kraamverzorgster) is provided for all new mothers to provide postpartum care, to help with breastfeeding problems, keep an eye out for postpartum depression, help with household chores, host guests and cook, and demonstrate the basics of baby care like bathing.

The Dutch also believe “happy parents make happy kids”. Women in the Netherlands are happier than women in other countries and research shows this is down to “personal freedoms they enjoy and a good work-life balance”. I love this quote: “Dutch moms have re-defined the meaning of having it all. They have plenty of time for their children; they can choose to stay at home, work part-time or full-time, according to their own preference, without financial or social pressure”. I’m not sure if it’s 100% true that no Dutch mother feels like they have to go to work even part-time because they need a little extra money for the family, but I do appreciate the lack of social stigma that the author’s describe if a mother decides she wants to stay home with her kids and take time out from her career for a couple of years.

“The negative effects of parenthood on happiness were entirely explained by the presence or absence of social policies allowing parents to better combine paid work with family obligations. This was true of both mothers and fathers. Countries with the better family policy packages had no happiness gap between parents and non-parents.”

Based on research by the University of Texas

This is helped by the fact that “men are doing more cooking and cleaning, and the time women spend on such activities is decreasing”, which alleviates pressure on women in the household. 75% of women and 27% of men work part-time (less than the maximum 36 hours per week), and this is possible in both unskilled and professional sectors. In the Dutch context, “being a housewife was a luxury: as soon as people could afford it, the woman would quit paid work”. In the Netherlands, parenting is seen as “something for which the whole society takes responsibility”, subsidized creches and camps, state education and healthcare, rather landing the responsibility only on the individual parents. These factors can make “all the difference for a happier mom”.

2. Protecting sleep

The Dutch are “uncompromising about the sanctity of sleep” and advocate the cry-it-out method to teach the child there is “no room for negotiation”. Some parents are not a fan of this approach, but it seems to have advantages since “at six months, Dutch babies slept an average of two hours longer than a comparison sample of American babies — 15 hours a day in total, compared to 13 hours”. They also highly value regularity and routine.

3. The importance of play

“There’s no attempt to teach the letters of the alphabet or numbers. What playschool is all about – true to its name – is play”. Development of social skills at an early age are very important: “how to make friends, take turns, be nice, and how to play with each other… how to share, be patient, be confident… how to express their feelings clearly… developing as a person and learning to speak their own mind”. There is also “a social pressure to be as average as possible and to never show off. This explains the lack of mompetition”. It probably also helps create a less competitive and more collaborative environment for children’s learning.

There are small parks “on the corner of almost every street in Amsterdam” and “children will happily play in the rain” and almost all weather unsupervised. The motto is: there is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing. Outdoor play also teaches independence, responsibility and grit and is good for developing social skills and problem-solving without adults present. It also helps kids “invent their own amusements” that stimulates their “creativity and ingenuity”. Dutch kids are not over-scheduled with after-school and weekend classes and groups and camps and sports and lessons etc., they enjoy play-dates to actually play as kids love to do. As the experts note: “children learn best through play and this has long-lasting consequences for achievement and well-being”.

A most interesting point the author’s highlight is that “what might look, from the outside like easy-going, relaxed parenting is often quite challenging for the parents involved. They have to make a conscious decision to let go of their own fears in the interest of their child”. This is a helpful point to remember throughout the book, that restraint by the parent can help increase independence and calmness in children, even though it’s not always easy to take a step back.

4. Enjoying school and learning

“It isn’t all about getting straight As and getting into the right university”. Education has a different goal in that it is a means for supporting a child’s well-being and the development of their sense of self. Metrics such as “how polite and helpful they are, how cooperative, how resilient, how motivated, perseverance and good listening” are important.

While children start school at the age of four years, they don’t begin learning to read, write or do arithmetic until they are six years old. But “if they do show interest in these subjects earlier, they are provided with the materials to explore them for themselves”.

“There are two kinds of Dutch higher education qualifications: research-orientated degrees offered by universities and profession-orientated degrees offered by colleges. You don’t need specific grades to gain admission to most college programs: all you need is to pass your high school exams at the right level – this is enough to guarantee a place.” “The [concept of the] “golden mean” reverberates through all levels of the education system in the form of the central objective of delivering a maximum number of pupils and students with a qualification” which improves the country’s prosperity and well-being by “keeping as many kids as possible in the race for as long as possible”.

5. Discipline

It’s a child-centered culture. “Play is considered more important than being quietly obedient” and “children are expected to be friendly and helpful towards their elders but not to automatically defer to them… Learning to put forward a good argument is a useful life skill and so is encouraged”. In terms of discipline, they “focus on teaching a child what’s right, through showing not telling, explaining not punishing… Responsibility and a good relationship are desirable [between parent and child]; authoritarianism is not”. Consultation and negotiation are the way to go, but as the author’s note, “it’s not for the faint of heart!’

6. Grit

Biking is the main mode of transport to get to school and the infrastructure is well set up to support this with bike lanes and bike sheds and staggered school arrival times. Although the weather is wet and windy often, the Dutch kids dress in warm clothes and waterproofs and brave the elements year round. These kids “learn grit” and resilience, which are positively linked with happiness. It also helps kids become “responsible and independent”. This introduces a healthy start to the day, helps reduce obesity rates, and provides kids freedom since they often bike themselves or with friends.

7. Simplicity and frugality

“One has the right to brag about how much one saves and others will listen”. The Dutch enjoy camping, for example, because it is a “way to have fun with the family while staying true to the Dutch pastime of bezuinigen – thriftiness” and also being close to nature, enjoying the simple things in life, and offering kids a lot of freedom. They are frugal also with gifts and pocket money, but very generous with charitable donations – they donate more to charity than any other country in the world (this number must be per capita rather than total, even though the authors don’t mention that) and charitable work. “There’s no attempting to outdo the Joneses” at birthday parties, and kids are used to having secondhand toys and clothes.

Contrary to many other Western nations in recent decades, inequality has not risen in the Netherlands. One of the biggest factors in the deterioration in relationships in society is inequality – it increases competition, feelings of inferiority, jealousy and anxiety and Dutch kids face less of this than many kids in other countries. “What Dutch children grow accustomed to in childhood sets them up for life: they are pragmatic and confident, unhampered by anxieties about status”.

8. Eating together

“In no other country do families eat breakfast together as regularly as they do in the Netherlands”, and Oxfam’s research declared the Netherlands as having the best food in the world: it is plentiful, affordable, good quality and doesn’t cause high rates of obesity and diabetes. Eating dinner together is also very important – they believe this is the place where “children learn to have their own opinions and express them”, to engage in conversation and connect on the day’s experiences.

“Research undertaken in the US shows that the way a family dines is a powerful predictor of how children will develop: kids who eat dinner with their parents at least 5 times a week were less likely as teenagers to smoke, drink, use marijuana, get into serious fights, have sex, or be suspended from school, and were more likely to go to college.”

9. Sex, Teenagers and Revolution

As you might expect due to stereotypes of the Netherlands, there are no taboos subjects about sex. Teenagers should feel free to ask questions and expect them to be answered honestly and openly. “Teen sex is allowed, but they prefer it to be in a controlled environment, that is, under the teen parents own roof… a safe place to have sex encourages safe sex”. The authors also believe that children have healthier gender role models, there is an absence of ‘”lad culture”, women and self-assured and men are involved in taking care of the household, and homosexuality is in the open.

The authors describe how Dutch parents create “zones of order” in which teenage experimentation is tolerated but monitored”. Their mindset is more “permit it, hug it close, control it”. An article by Kuper in the Financial Times says ” the Netherlands has done everything possible to make teen sex and drugs seems dull”! They also mention the importance of trust between the parents and teen to encourage them to become independent, responsible, and good problem-solvers for themselves. Parents focus on positive encouragement rather than negative punishment to help their kids grow independent. Schools also get involved and providing support through ‘faalangst’ – fear of failure – and helping teens overcome this. They advise not to check in on them, not to nag them, not to discourage them, or expect them to be like you and accept them for who they are.

Comparison to UK parenting

As a child with British parents, and who grew up in a part of the UK in the 1980s and 1990s, one of the things that concerned me about the way the authors describe British parents is that they appear to assume they are a monolith. This is not the case for any group of parents – whether it be those in the UK or in the Netherlands. While I understand the benefit of creating and/or drawing on broad-brush truths or stereotypes of a culture in order to make it accessible, consumable and digestible to a wide audience, there are risks in over-simplifying and missing important nuances.

I am unfamiliar enough with the Dutch culture of parenting, but have intimate knowledge and first-hand experience with British (which is worth highlighting includes four nation states of Scotland, England, Northern Ireland and Wales) parenting, and my experience was very different to that described in the book. There was no great pressure of high achievement at school; there was mainstreaming (at least until age 11) of the intellectually smart, average and challenged at schools that reduced competition; many mothers stayed at home or were part-time workers; we ate dinners together; and there were many parks where kids played unsupervised (over the age of about 5 years) and outside in almost all weathers – certainly in the rain and wind!

So this leads me to ask of the authors, has there been a generational shift in the way that kids are raised in the UK – and the answer to that would probably be partially yes. The bigger question being ‘why’? Why has the UK chosen to take its families in the direction that it has? And if the UK has experienced a dramatic shift in the way that parents raise children in the UK, some of the factors I imagine affecting that are also affecting many other countries in Europe and possibly around the world.

I am thinking, for example, of the increased participation of mothers in the paid employment workplace, kids gaming technology, more reliance on cars to get around now… If this is the case, how do the Netherlands opt out of going in that direction? Some characteristics that are discussed in the book are frugality, no stigma for mothers who decide to stay home, no growing economic inequality, vacationing close to home and camping, second-hand clothes and toys, not purchasing and running a family vehicle other that a bicycle. Adopting this lifestyle affords a level of financial freedom that allows for a more relaxed lifestyle and greater time by the parents at home or on vacation with the kids.

One comment that I have on the comparison to parenting in the UK is that I only remember reading reference to friends and family living in London. Given the high cost of living in London relative to most other parts of the UK (and world!), there is possibly greater financial pressure on parents in London than elsewhere in the country, and this may lead to different parenting decisions. The average Londoner also has a notoriously long commute compared to workers in many other parts of the country – this is a massive time suck that London parents have that some others do not. It would have been interesting to include testimonies and experiences from parents in a few parts of the UK other than London to have a more true reflection of UK parenting, rather than taking the London experience as the norm and holding that up as the stressed out, tough UK experience the authors say it is compared to the Netherlands.

Overall, I felt the comparison to the US and UK were described in a somewhat binary way – Netherlands experience is good, UK and US experience is bad. Most things in life like parenting tend to operate along a spectrum, rather than in extremes, and I would have appreciated if the authors had been better able to carry some nuances in their messages. It felt like a little bit of a sales pitch for the Netherlands!

I also don’t think that it was particularly beneficial to lump the US and UK together as being very similar. Having lived in both countries for many years, I think there are large differences in the national systems, the cultures, values and norms around parenting, child care and education systems, and economic inequality. However, they are, for sure, more similar than some other countries – and I understand that by virtue of the fact that the authors originate from these two countries it made sense to draw on these places as their point of reference.

Some Dutch parenting tips for the non-Dutch

Having a scan through some of “The Happiest Kids” book reviews on goodreads.com I found one repeated criticism was that while the book was enjoyable and the Dutch parenting lifestyle sounds great, most of what is mentioned cannot be transplanted into their own lives in their own country.

So, I would like to challenge that and offer a few suggestions, from what the authors write, that I believe can work in other countries and cities.

‘Good enough’ parenting mindset: We can take control of what is in our mind and try to side-step or minimise our feeling of ‘needing to do it all and needing to do it perfectly in order to be great parents’ approach. We can also be consciously aware to try and avoid being drawn into the competition that can exist amongst parents and kids in schools and social settings.

Lots of outdoor play: It is not common in the US, for example, to let kids out to play in the park on their own. A friends kids were stopped by a police car and asked where their mother was as they simply walked home from school aged 8 and 5 years, and were only 5 minutes from their door. I couldn’t believe it when they mentioned Child Protection Services to my friend! However, it is possible to ensure kids have lots of time to play outdoors in their garden or a friends garden without supervision, or at the local park with supervision. This helps kids to gain greater knowledge of the outdoors, allows them to experiment with physical activities, and is character-building in fostering grit by playing outdoors in tough weather. I was surprised in the US how quickly the schools close with only one or two inches of snow – in the UK we were still walking to school through the snow and having a great laugh on the way!

Frugality: It’s possible to share baby and kids clothes among friends, community organisations, online, yard sales etc. to reduce the cost of many kids items. It is also possible to take the family annual vacation to a campsite – of which there are many, many beautiful spots all over the US. For some families, doing so can alleviate financial pressures a little, creating a little less need for two full-time incomes.

Bicycle culture: Even although the US cities and suburbs have been designed in the past century as heavily reliant on its car culture, it is possible to live the bicycle lifestyle. There are parents in the US city we previously lived in who have their home in the city, send their kids to public or charter schools in the city close to where they live, and bike, bus and metro around town to work and social events. This does require a specific lifestyle choice that may not be aligned with previous decisions (i.e. where you bought your house), but for the nay-sayers I’m just highlighting it is possible to do within the US.

And, of course, there are many changes that would take a collective movement and many years rather than individual efforts in the short-term to make change and introduce similarities to the Dutch system. For example, advocating for subsidized child care policies, or advocating for change in the national education system that would cause less competition and pressure on intense academics (Chinese kids, for example, are amongst some of the most academically pressured and stressed-out kids in the world). There is no quick or simple fix to changing the mindset and focus of a nation’s child care or education system.

Happiness or Well-being?

For those still reading and interested in the rapidly growing field of ‘happiness science’, I decided to keep this end note… One thing that is interesting to think about (please excuse any pedantic geekiness here) is how we talk about happiness. The founding claim of The Happiest Kids book is that “in 2013, a UNICEF report rated Dutch children are the happiest in the world“, is that the authors imply that well-being [that was measured in the UNICEF data using indicators above] is the same as happiness [that is not measured in the data, and some would say is too subjective to measure as it is a state of mind].

One might ask if the author’s claim about happiness can really be based on a UNICEF report on well-being? Are happiness and well-being synonymous? Many researchers working in this field would say not so – that well-being can be one part contributing to overall happiness and that well-being “denotes a kind of value” that “benefits of harms you, or makes you better or worse off”, but is not synonymous with happiness. Others, for example those working on the World Happiness Report, however, believe that it is possible to use a set of measurable indicators, for example, on economic wealth, life expectancy, freedom to make choices to use as proxy indicators that provide an accurate measurement of happiness.

The UNICEF authors themselves admit that “on each of the indicators used, the measurement and comparison of child well-being levels across different countries is an imperfect exercise with significant gaps and limitations. Ideally, it would also require better and more child-oriented data on such critical important indicators as: the quality of parenting; the quality as opposed to quantity of early childhood education; children’s mental and emotional health“… the latter of which would no doubt include reporting of feelings of happiness.

A recent article in the Telegraph continues the conversation asking “are Dutch kids really happier?“.

What do you think: are they really happier? Do you agree with the authors findings that these factors are what make children happy? Were these factors present or not in your childhood? Are well-being and happiness synonymous to you?